Horu Ka Nahkt, Tut Mesut - "Horus, the strong bull, beautiful

of birth" (this

is his 'Horus name', identifying him with Horus, god of kingship)

Nebity Nefer Hepu, Segereh Tawy, Sehotep Netjeru

Nebu - "Goodly of laws, who calms the Two Lands, who placates

the gods"

(his 'Nebity' name, identified with the two

goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt)

Utjes Khau, Sehotep Netjeru - "Exalted of crowns, who

placates the gods" (the 'Horus of Gold' name)

Nisut Bity, Neb Kheperu Ra - "King of Upper and Lower Egypt,

Lordly Incarnation of Ra" (this was his throne name, which, along with his

personal name, was most often used)

Sa-Ra, Tutankhamun Heqa Unu Shema - "Son of Ra, Living Image

of Amun, Ruler of Thebes"

It is interesting to note that the king's birth name was actually TutankhAton, but two years into his reign his name was changed to reflect a shift in theology.

Tut is often called the "Boy King" because he was coronated when he was only eight or nine years old, and he ruled for only ten years before dying suddenly at about nineteen. Today we consider someone that age to be just a teenager, but in his day someone aged nineteen was considered a grown man. In fact, the mummies of two stillborn baby girls were found buried with Tutankhamun, and recent DNA studies, hilighted on the Discovery special King Tut Unwrapped, have established that those were his children. So the moniker of "Boy King" is actually a bit misleading, because at the time of his death we can gather that he was considered an adult and was trying to start a family. Scholars had also debated whether or not he was murdered. Recent, state-of-the-art CT scans revealed that Tutankhamun suffered a broken leg shortly before his death - which he might have survived, were it not for the infection of Plasmodium falciparum, or tropical malaria, that DNA tests revealed he also contracted around the time of his death. P. falciparum is the most severe form of malaria, and it still claims many victims in developing countries even today.

The identity of King Tut's parents has also been a subject of debate, but the DNA tests also finally established that his father was King Akhenaton - who is also called the Heretic Pharaoh because he shut down all the state temples devoted to the god Amun in favor of another god, the sun deity Aton. Some scholars say it was purely religious innovation while others think it was more of a political move, but in either case, Akhenaton was hated by a lot of people after he died. His name was erased from monuments and public records, but not until after Tutankhamun's death.

King Tut's body still rests in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Until 2007 he lay inside one of the three mummy-shaped, or mummiform, coffins in which he had originally been buried. This gilded wooden coffin in turn rested inside his quartzite sarcophagus, covered by a thick pane of glass. But due to concerns about the preservation of his mummy, in late 2007 King Tut was placed in a special climate-controlled glass display case set up in his tomb. You can watch the video article about his official unveiling here.

We also know that in life he stood about five-foot-seven with a slender build. He had a slight deformity in his left foot, which in his adolescence developed into Kohler's disorder, a rather painful condition in which bones in his metatarsal joints deteriorated. Today these conditions can be successfully treated, but during Tutankhamun's lifetime he had to use canes or walking sticks for support. In fact, he was laid to rest with well over a hundred of them, including a gold-capped river cane bearing the inscription, "Cut by His Majesty's own hand".

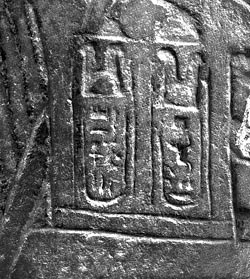

The Pharaoh's

name and throne name were carefully chiselled into the seam of a statue, as

shown in this photo, that was usurped by one of his successors in the inscriptions

on the front. Someone evidently defied a royal order in an attempt to preserve

the name of Tutankhamun for posterity. Chances are that whoever it was would

be pleased to know that his Pharaoh is now world-famous.

The Pharaoh's

name and throne name were carefully chiselled into the seam of a statue, as

shown in this photo, that was usurped by one of his successors in the inscriptions

on the front. Someone evidently defied a royal order in an attempt to preserve

the name of Tutankhamun for posterity. Chances are that whoever it was would

be pleased to know that his Pharaoh is now world-famous.

If you're interested in reading further, here's our bibliography of scholarly sources. Note these are actual books, which you can either purchase online or look up in your local library:

Desroches-Noblecourt, Christiane. Life and Death of a Pharaoh, Tutankhamen. London, 1963.

Gilbert, et al. Treasures of Tutankhamun. New York, 1976.

Reeves, Nicholas. The Complete Tutankhamun. New York, 1999.

Back to the Temple main page